WARFARE IN WEST SUSSEX

In June 2015 Haywards Heath Town Council installed a lectern on Muster Green in the town, to commemorate the English Civil War battle there in 1642. I was the one who had suggested this step to the Council and at their request composed the inscription. But actually this came about by accident, from when I was researching a historical event six miles away in West Hoathly.

In 2012 I was writing my book Mysteries of History in Sussex and included a chapter on a fascinating riddle about West Hoathly, which must be one of the most beautiful and tranquil spots in Sussex. The village stands 600 feet up on the ridge of the High Weald, the wooded and shady churchyard spreading south from the church and then suddenly dropping down by terraces into a deep valley. At the point where this descent begins there is a seat from which the visitor can admire the view southwards across the weald and towards the South Downs, some fifteen miles away. Set in the wall behind the seat there has been, ever since I can remember, a stone inscribed with the lines:

Friend, looking out on this wide Sussex view,

Know they who rest here looked and loved it too:

Pray then like them to sleep, life’s labour past,

In your remembered fields of home at last.

But there is evidence in this peaceful place of a dramatically violent past. In the church there is a simple and tiny brass tablet memorial to Anne Tree, a villager who was a Protestant martyr burned to death for her faith in nearby East Grinstead in 1556. More recently, when I was young, the graves of two Second World War German bomber crew members lay on the southern edge of the churchyard, at the bottom of the valley, their aircraft having crash landed locally. The graves are no longer there and I have been told that the remains were at some point repatriated to Germany.

But the mysterious conflict, if there was one, dates from the seventeenth century. The great wooden door of the church has a date in large letters consisting of iron studs, MARCH 31 1626. The door also features, around its upper right hand side, half a dozen semi-globular indentations, roughly about the size of Maltesers. Like the surface of the door around them, they are smoothed and shiny with age. When I first visited, as a child with my father, he told me that they were musket ball holes made by parliamentarian soldiers in the English Civil War, firing as royalist soldiers retreated into the church slamming the door behind them. He said he had been told this a few years earlier by the landlord of the Cat Inn in the village, while he was having a drink there. The present church guide makes no mention of the holes, but an earlier version (1976) briefly stated that they were said to have been made during a local skirmish between Cavaliers and Roundheads. I have visited the village many times in recent years and local people say they know the story but have no idea whether it is true. One villager even said perhaps the holes stemmed from a shotgun wedding where the firearm was actually discharged!

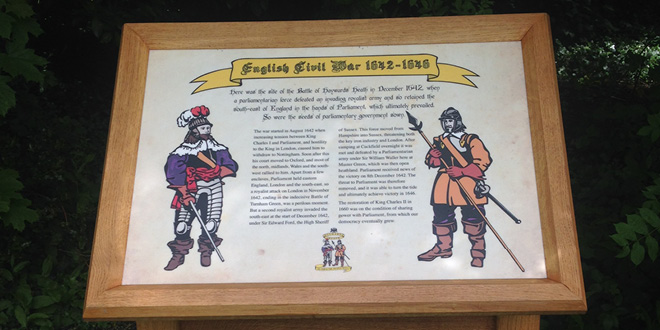

So I decided to explore how likely a Civil War engagement at West Hoathly might have been. I discovered that Sussex was in the east and south-eastern part of England that was controlled by Parliament, and that in December 1642 a royalist force invading from the south-west was defeated at Haywards Heath. It struck me that given the proximity to London, the hinge of parliamentarian territory, and the Sussex iron industry, this must have been strategically more important than the footnote in history it has been up to now. It also seemed to me that a satellite skirmish six miles away, at West Hoathly, would not have been at all unlikely. In fact thinking about it, the contact could have been parliamentarian soldiers rounding up fleeing royalist soldiers, which would tally with the local tradition of the one group firing muskets at the other group as they fled into the church and slammed the door.

I found though that there was a second royalist invasion of Sussex a year later, in December 1643, raising the possibility of a clash at West Hoathly then. The record shows this army capturing Arundel castle in that month, but only to be besieged and to capitulate the following month. There is also archaeological evidence from this period of fighting at Greatham, whose medieval bridge still spans the river Arun six miles north of Arundel. It seems that some of the invaders got further because at exactly the same time as the conflict at Arundel another engagement was taking place a dozen miles east, ie further into Sussex, on the river Adur. This was recounted in letter from a John Coulton to a Samuel Jeake of Rye dated 8 January 1644 :

The enemy attempted Bramber Bridge, but our brave Carleton and Evernden with his Dragoons and our Coll.’s horses welcomed them with drakes and musketts, sending some 8 or 9 men to hell (I feare) and one trooper to Arundel Castle prisoner, and one of Capt. Evernden’s Dragoons to heaven.

The correspondents sound like puritan sympathisers, and by this time Arundel castle was just back in parliamentarian hands, so a prisoner sent there would be a royalist. If so, this records a successful resistance to royalists trying to push eastwards at a key point, a bridge over the river Adur.

But these events were all at places twenty miles west of West Hoathly and there is no record of the royalist incursion advancing any further. So it seems much more likely that any conflict at West Hoathly would link with the battle at Haywards Heath a year before. It does also seem likely that there was an armed clash, as it is difficult to see what else might have caused the holes – which are the right size for musket balls (not shotgun pellets!). It is impossible to think of any other conflict between the age of the longbow and the age of the rifle in which an armed exchange might have happened.

So I think the oral tradition in the village is right. There is too one other interesting link. We have seen above the role of a Captain Evernden and his dragoons at Bramber, but another source also links a Captain John Everinden (sic) with West Hoathly. In November 1643, two months before the action at Bramber, he and his dragoons are the ones to evict the Anglican vicar of West Hoathly in favour of a puritan preacher. Fortunately for the vicar, though, the lady who owned his house assured him that he, and not his puritan replacement, could still live there!

It would be interesting to know more about this firebrand captain of dragoons – including whether he has any link to a seventeenth century house in Lindfield called Everyndens. As so often, finding an answer to one mystery opens up another.

PHILIP PAVEY